Totem Poles of the Pacific Northwest

Note about Pictures: In order to make room for so many photographs, I’ve had to use thumbnails – I hope readers will click on some of them to see them full-sized.

The coastal region of the Pacific Northwest, stretching from the Alaskan panhandle in the north to Vancouver Island in the south, has been home to indigenous peoples for thousands of years, including the Tlingit (pronounced kling-KIT), Haida, Tsimshian and Kwakiutl.

These are different groups with distinct histories and languages, but they share deep similarities of culture, religion and art, which combine to constitute what the great anthropologist Franz Boas has called “one of the best defined cultural groups on our continent.” (Social Organization and Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl, 317) I will speak most frequently of the Tlingit, but draw upon other groups participating in this common cultural heritage as well.

One of the most striking features of this cultural zone is what we will call totem poles for lack of a better term. The word “totem” comes from the Ojibwe word for “kinship group,” and does not properly belong to the region. The Tlingit term is kootéeyaa, but several natives I have spoken with used the term “totem pole,” so I will follow their lead.

Originally, most totem poles were probably carved into the pillars of clan houses, like the great totems flanking the magnificent Beaver screen in the Tlingit Beaver Clan House of Saxman, Alaska (shown to the right). Short, free-standing totem poles were also placed in the woods, used to house the cremated remains of venerated persons.

When Russian and European fur traders arrived in the nineteenth century and metal tools became widely available, it became possible to carve much larger poles. These massive poles, sometimes dozens of feet high, were commonly erected along waterways, as the people inhabited narrow strips of land between the coastal mountains and the sea, or in densely-forested river valleys, and traveled by water.

The oldest surviving poles date to the mid-nineteenth century, and those are relatively few in number. Poles are usually carved of cedar, which does not preserve well. However, my understanding is that the demise of a pole is regarded as the completion of its life cycle, not a tragic loss.

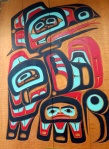

Totem poles are emblazoned with figures called crests, which are usually animals, mythological beasts or legendary ancestors. Crests form an integral part of the social and symbolic economy of the Pacific Northwest and are core features of social identity. A crest may only be displayed by a family that owns the right to the crest, and those rights are passed down.

One interesting exception to that rule is the owl crest, shown to the right, which is not inherited and may only be displayed by a shaman.

Crests often signify historical or legendary episodes that help define the identity, status and privileges of a family. The world of songs, legends and myths is intimately bound up with crests, which may explain where the clan came from, why they have the right to fish in a particular stream, and so forth.

Let’s take a look at the striking Eagle Halibut pole of Laay, currently on display at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, to get a sense of how the symbolism works. The interested reader will find the full account of this complex pole here, but I will only focus on part of it.

To the right you will see two crests that combine to form a single composite image at the base of the pole. The smaller crest depicts a hero named Gunas being devoured by a large halibut, and that image is set onto the chest of a larger figure, an intense-looking figure called Hagwil̓ooḵ’ who carries a bent-wood box on his head.

This is a memorial pole for the Tlingit Chief Laay, who led his people out of their original home in Alaska to the village of Gwinwoḵ on the Nass River in Canada. While they were traveling to their new home, Gunas went swimming in the clear waters near Cape Fox, when he was suddenly attacked and swallowed whole by a giant halibut.

Richard Morgan tells the story:

Everybody got excited, you know, when they saw the huge halibut. They called for Supernatural Halibut and they called for Supernatural Eagle to help them. And the eagle [was] sitting right at the point, and the next thing you know, the eagle managed to get the halibut ashore and capture the halibut. And they cut the halibut open, but the body of Gunas, the remains of the body, [were] already decayed, so they sing a dirge song, funeral song about Gunas being captured alive by a halibut.

This account is typical of crest legends in several ways. It links an episode of the legendary past with a story and a song, and establishes the debt owed by the halibut to the clan. The Gunas crest connects the Nisg̱a’a Tlingit to halibut fishing – Gunas paid for the crest with his life. Crest stories frequently involve someone owing a debt, or violating a taboo or getting into a disagreement with an animal power or deity, and being killed. This death creates a new debt in the symbolic economy, and and the family earns the right to a story, or song, or place, or the right to hunt a particular animal, et cetera.

The concepts of debt and exchange are extremely important in the Pacific Northwest, as we saw previously when we looked at shame poles, which are erected to commemorate unpaid debts. The flip side of this is that if you want to fish, your family needs to have the moral right to fish, and it often seems to be established in stories of this kind.

There is a deeper mythological sense to this pair of images as well. Gunas and his halibut are engraved on the chest of this scary-looking Hagwil̓ooḵ’ fellow. Morgan explains this figure thusly:

And as they [were] traveling, they encountered a huge man from under water. It has a tail of a salmon. It came up with huge spring salmons, huge seafood, a lot of seafood. They call it Hagwil̓ooḵ’. That’s a symbol you will see on the bent boxes. Anybody who is really aggressive, get a lot of food for families, they call them Hagwil̓ooḵ’.

The paired crests of this pole combine the two aspects of the Great Hunt in a single image – we see both predator and prey. The Nisg̱a’a has paid for the right to catch fish with their own flesh and blood; that is, they belong to the cycle.

We’ve looked at this basic tragic image several times in this blog, most recently in the Grimm Brothers story “The Juniper Tree” here. We’ve also looked at the symbol as it was expressed in Iron Age Greece here.

The Eagle Halibut Pole of Laay illustrates the whole symbolic economy of the Pacific Northwest. Clans are characterized by the of symbols that encode their history and establish their rights and powers. These crests are not only displayed on house pillars and totem poles, but found on ceremonial chilkat robes or button blankets worn during ceremonial dances. A Tlingit can tell at a glance where someone is from and what their lineage is, simply be looking at their regalia.

Despite various historical challenges and setbacks, the symbolic culture of the Pacific Northwest remains vital and active to this day. While indigenous populations were decimated by exposure to Old World diseases such as small pox, the numbers have now stabilized. The United States abandoned its disgraceful campaign to eliminate native languages and cultures in the region decades ago, and since the 1960s there has been a great revival of interest in native art and culture. So the old arts are carried on – to the right you can see Tlingit Master Carver Nathan Jackson at work on a new pole in his studio. He was the lead artist of the spectacular Beaver Clan House screen shown above.

Many new artists appear to be interested in incorporating new sources of inspiration and ideas. For example, the superb Kwakwaka’wakw artist Doug Cranmer spent several years in the 1960s using traditional compositional elements of the Pacific Northwest to create entirely abstract work without story or reference. I also enjoyed the work of Averyl Veliz that I saw at the Juneau-Douglas City Museum, such as her wonderful “Wolf in the Moon” (right).

A great example of the harmonious blend of old and new is The Raven and the First Men by Haida artist Bill Reid, currently on display at the University of Anthropology in Vancouver. This magnificent carving depicts a Haida myth of Raven acting as a kind of midwife for the creation of humankind.

Raven is a powerful shamanic trickster figure and is the culture hero of the entire vast region from the Kwakwaka’wakw of Vancouver to the Inuit of Alaska. His stories are especially connected with acts of creation and naming, and the story of how Raven stole the sun from heaven and ended the long darkness is an extremely popular subject. In my next post on the Tlingit and other traditions of the Pacific Northwest, I’ll have a closer look at the mythology of the region, with particular attention to Raven.

The traditions of the Northwest remain with us. Bertha Sleid Guan of the Kaagwaantaan Tlingit told me that in her village, public schools offer classes in the Tlingit language every day, and once a week, the entire school day is conducted in Tlingit. She described her sense of wonder at seeing a young Tlingit girl speaking in her own language with her schoolmate, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl of Norwegian descent.

I told Bertha that I had read many wonderful stories of the old days, like the story of how the Tlingit came to move out of their ancient home in Glacier Bay, which I read in the superb book Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors by Norma Marks Dauenhauer and Richard Dauenhauer.

As Susie James told those authors, the Tlingit used to live in peace and abundance in Glacier Bay. At that time, there was a young girl who was kept in seclusion behind her house. We learn from many ethnographers such as Kalvero Oberg that this was a common practice when Tlingit girls approached adolescence. They were sequestered for months or a year in a private little hut behind the family dwelling until they were presented as adults at a great feast or potlatch.

But this girl was kept there for three years, which is a very long time. One day she saw a glacier very far away, and perhaps because she was unhappy with her seclusion, she called to it like a dog, saying “Glacier, here, here.”

To everyone’s alarm, the glacier started to grow, started to advance on the Tlingit, fast, faster than a dog could run. Everyone saw it charging toward them and they got into their boats to flee, to leave Glacier Bay and find a new place to dwell — everyone except for grandmother who didn’t want to go. She said “I will stay here. Whatever happens to my mother’s maternal uncles’ house will happen to me.” So she stayed and gave her life to the glacier, and there is our debt.

When I spoke to Bertha, I told her I had read this story, and I wanted to know, how do the Tlingit hold these stories today? Are they valued as legends, or are they believed, the way history is believed?

She told me that it may be hard for you to accept that a glacier would run as fast as a dog, but we’ve researched the area and we know that the Tlingit of her village came down from Glacier Bay, and they regard it as their sacred home. The archaeological evidence indicates that the area was inhabited around 2000 years ago by a people evidencing cultural continuities with the Tlingit of today, until they were driven out by a long period of ice. When the glaciers receded after the end of the Little Ice Age in the Middle Ages, the Tlingit appear to have moved (back?) into the area.

She told me that there are many stories that can be told to outsiders, like the ones I read in my book, and many songs that are sung for anyone. But then there are stories and songs that are private, known to the families and houses, and those stories have a lot to say about the world, and who we are.

All photos are (c) Barnaby Thieme, except “Wolf in the Moon,” which is my photograph of a work by Averyl Veliz, who retains all rights.

Thank you! I look forward to your piece on mythology. I especially appreciate your information about glacier bay–I had not known of that story. Anne

Anne Campbell

July 22, 2012 at 12:07 pm

Thanks for the kind support! I’m very pleased you liked it.

mesocosm

July 22, 2012 at 12:10 pm