Posts Tagged ‘tlingit’

The Raven, the Bear, and Shamanism in the Pacific Northwest

This post may be read on its own, or as a continuation of “Totem Poles of the Pacific Northwest.” Please click on thumbnails for full-sized images.

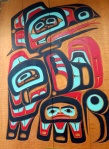

Raven is the great culture hero of the Pacific Northwest, a trickster who figures prominently in myths ranging down the coast from the Arctic Circle to Vancouver.

Raven is a complex figure, but in this analysis I’d like to focus on his role as the exemplar of shamanism, the dominant religious culture found throughout the region. By examining Raven’s shamanic character, we can ground the Pacific Northwest in a circumpolar cultural horizon of great antiquity, with roots that reach back more than 35,000 years to the Upper Paleolithic.

Here is the story of how Raven came into the world, according to the Tsimshian people of British Columbia:

Once upon a time, when the world was still covered in darkness, a chief and his wife dwelt in the town of Kungalas with their only child, a boy whom they both adored.

When the boy had grown large, he fell very sick, and soon died. His parents mourned with bitter tears for their beloved boy, and invited all of the people to come and see his body where it was laid out. The chief ordered his son’s intestines be removed and burned, kept vigil with the body for many days.

One morning, before dawn, the chief’s wife went to the body and found a youth, bright as fire, lying where the corpse had been. She called to her husband “Our beloved child has come back to life!”

The shining youth said “Yes, it is I,” and explained that heaven had grown weary of the wailing of the mourners, and sent him back down to live again.

The parents were overjoyed by this miracle, but it soon became apparent that the shining boy was not like the son they had known. Day after day, he refused to eat, giving his food to two household slaves, who were together known as Mouth-At-Both-Ends.

One day, the chief found the corpse of his son stowed in the back of the room where he had been laid out, and realized the shining boy was not his son. But he loved the shining boy and would not give him up.

Now, the boy had been watching the household slaves eat ravenously, and asked why they felt such hunger, and if they enjoyed eating. Surely they did! they replied, and told the boy that hunger had entered them when they tasted the scabs from their own shin bones.

The boy decided that he, too, would taste the scabs of their shins, and when he put a tiny piece of flesh from Mouth-At-Both-Ends into his mouth, he became ravenous and began to eat. He ate and ate, day after day, until all the food of the village had been eaten.

The chief knew he must send the boy away, or he would eat everything. He told him to fly over the sea, and gave him all kinds of berries to take, saying that the boy should scatter them about so that they would grow everywhere and he should have food.

So the boy took up his Raven mantel and flew away from Kungalas and entered the lands we know. (1)

The basic features of the story are easy to interpret – the shining boy comes from outside the normal order of things. In order to fully enter the material world, he must partake of the flesh of Mouth-At-Both-Ends, the pair who collectively embody eating and elimination and, as such, embody the cycle of carnality.

Other features of this story may strike the reader as bizarre, such as the boy’s sudden sickness, the removal and the burning of his intestines, and the substitution of the shining boy for the corpse.

To explain those images, we have to dig into ancient strata.

These symbols commonly occur in the initiation imagery of shamanism, which refers to a number of related visionary practices undertaken by a solitary adept. The shaman uses a variety of techniques to enter into trance states, during which he may travel into the sky, under the earth or into the sea, often assisted by animal guides. He uses his abilities to heal the sick, control weather, attack his foes, find lost objects, and so forth.

Shamanism comes from ancient traditions of Siberia, such as we find among the Yakut and Tungus peoples, and its basic symbols are extremely old. Indeed, the earliest-known cave paintings, dating to the Aurignacian period beginning some 35,000 years ago, have been interpreted by leading experts as shamanic in character (2).

Cave paintings usually depict animal, especially images of the hunt. Cave lions pursue aurochs and horses, while bears, rhinos, and cave lions stalk the shadows.

In paleolithic cave art, we find a number of animal images strongly associated with shamanism to this day, including the bear and the owl. In the post Totem Poles of the Pacific Northwest, we saw that the owl crest is claimed by Tlingit shamans alone.

This painting from the cave of Lascaux, approximately 17,000 years old, is frequently interpreted as depicting a shamanic trance. We see a disemboweled bison transfixed by a spear, and a man lying prostrate, perhaps in a trance, with an erect phallus. He has the face of a bird or is wearing a bird mask, such as the natives of the Pacific Northwest still wear in their sacred dances (see picture below). A bird sits on the top of a pole nearby, perhaps reminding us of countless bird-topped totem poles.

Another figure strongly associated with shamanism in paleolithic cave art is the bear. We find hand prints stamped on cave walls that have were slashed by cave bear claws, symbolically linking the shaman with the bear (3). The earliest human altars may have been cave bear skulls that were carefully set on rock pedestals deep inside the great caves.

We will return to the bear soon, but for now, to continue with our Tsimshian story of the Raven, the relevant point is that it contains unmistakable symbols of shamanic initiation.

In his definitive study of shamanism, Mircea Eliade has documented numerous accounts of the career of the shaman, drawn from cultures throughout the world (4). In all cases, the decisive event in the shaman’s development is the sudden call to his vocation, marked by abduction or ordeal.

In a typical case, the future shaman lives a normal life until the onset of adolescence, when he falls into a fever coma or vanishes from the village for months, having been abducted by superhuman shamanic masters. In Nepal, for example, young men are occasionally spirited away by the Yeti, properly called Ban Jhākri, and forced to toil miserably for years in payment for the magic songs they will need to practice their art (5).

Eliade quotes this account of a Yurak-Samoyed shaman, who experienced an initiatory vision after falling gravely ill. His vision culminated in this experience:

Then the candidate came to a desert and saw a distant mountain. After three days’ travel he reached it, entering an opening, and came upon a naked man working a bellows. On the fire was a cauldron “as big as half the earth.” The naked man saw him and caught him with a huge pair of tongs. The novice had time to think, “I am dead!” The man cut off his head, chopped his body into bits, and put everything in the cauldron. There he boiled his body for three years. (6)

Note the significance of the number three here, which reminds us of Jonah’s sojourn in the whale, or Christ’s period of entombment. The number most likely derives from the three days during which the moon is dark, until it is reborn into the light.

An Australian Binbinga shaman named Kurkutji met the old god Mundadji in his initiatory experience:

Mudadji cut him open, right down the middle line, took out all of his insides and exchanged them for those of himself, which he placed in the body of Kurkutji. At the same time he put a number of sacred stones in his body. (7)

The initiatory vision of shamanism across a great geographical region includes this common feature of being ritually dismembered or eviscerated, and then purified, often with a theme of substitution, as in the case of Kurkutji, whose innards were replaced.

This is just what we see in the myth of the raven, who appears as a substitute for the son who fell ill and died “once he had grown large,” i.e., at adolescence, and whose innards were excised and burned.

Eliade identifies shamanic motifs in cultures throughout the Americas, from the Bering Straight to Tierra del Fuego (8). The shamanism of the Pacific Northwest is largely organized around the mythology of the raven. As a carrion eater, Raven mediates between the living and the dead. As a bird, Raven mediates between the heavens and the earth, and embodies the shaman’s magical flight.

I cannot help but marvel at the close relationship we can uncover between our Tsimshian myth and the vision of a Bibinga shaman in Australia! That suggests a common ancestor mythology of enormous antiquity. The roots of this belief system were laid down before humans traveled over the Bering Strait, and before Australia was colonized.

During the twentieth century, a version of the shamanic bear cult was observed among the Ainu people of northern Japan. The Ainu were observed to periodically capture bear cubs and bring them back to their villages, where they were suckled by a human wet nurse and treated as beloved companions. When the bears became large enough to be dangerous, the villagers threw a feast for the animal, who was then ritually killed at the end of a going away celebration. The bear was expected to travel to the land of the gods, and to report that it has been treated well by the village. (9)

Let’s compare that ritual with a popular Tlingit myth concerning the hero Kats and his bear-wife.

One day Kats went bear hunting, which is a very dangerous thing to do. Now, he was going after a particularly large and ferocious bear, and he found himself forced into the bear’s den, where he came across the bear’s wife.

Kats and the female bear exchanged looks, and she fell in love with the hero. She took Kats under her protection, hiding him under the earthen floor of her den until her husband went away.

In some manner that the story doesn’t specify, the female bear eventually took leave of her bear husband and married Kats instead, and together they had three cubs.

One day, Kats began to pine for his old life, and he asked his bear-wife if she will let him visit his village. She was reluctant to let him go, for she feared that he would not return.

At last, she acceded to his wishes, but warned him not to speak a single word to his human wife. Kats agreed.

He traveled along the waters back to his old village, and there he saw his people on the shore, and sure enough, he found his human wife from his previous life. He calls to her, “Run to the village, and tell everyone that I’m trapped in the Land of Bears!”

But before she can say a single word in reply, Kats’ three cubs raced out of the woods, and slashed their father with their claws, and he fell dead. (10)

There is an interesting parallel here with the Celto-Germanic motif of the hero who journeys to the magic realm of the fairy queen, returning to the ordinary world only at the cost of his life, which we recently explored in our analysis of Tannhäuser.

I will note in passing that there may be a genealogical connection here, as the pre-Christian religion of the Celts, and especially that of the Norsemen of northern Europe, exhibit shamanic characteristics. For example, the Norse All-Father Odin boasts impressive shamanic credentials, such as the nine initiatory days he hung from a tree in order to purchase the power of runes.

The Prose Edda speaks of Odin’s two raven familiars:

Two ravens sit on Odin’s shoulders, and into his ears they tell all the news they see or hear. Their names are Hugin [Thought] and Mugin [Mind, Memory]. At sunrise he sends them off to fly throughout the whole world, and they return in time for the first meal. Thus he gathers knowledge about many things that are happening, and so people call him the raven god. (11)

In the case of Kats, the bear occupies a liminal position between the human and animal worlds, and the danger here is going too far outside the human order. In this sense, the bear is a mediating symbol; as the raven mediates between heaven and earth, the bear stands halfway between human and animal.

In a similar sense, the shaman inspires both authority and fear by living outside of the natural order of things. Among the Tlingit, the shaman was paid directly for services, unlike everyone else, who participated in a complex ritual system of gift-giving and exchange. When a Tlingit shaman died, he was buried outside of the village. (12)

The bear, like the shaman, is human-like, yet not human, and is therefore uncanny.

In this light, I think of Timothy Treadwell, the subject of Werner Herzog’s documentary Grizzly Man. Like Kats, Treadwell got too close to the bears, and like Kats, he paid with his life.

Many have observed that Treadwell went too far outside of the human world, with tragic consequences. An Alaskan observes in the film:

One of the things I’ve heard about Mr. Treadwell, and you can see in a lot of his films, is that he tended to want to become a bear. Some people that I’ve spoken with would encounter him in the field, and he would act like a bear, he would “woof” at them. He would act in the same way a bear would when they were surprised.

Why he did this is only known to him. No one really knows for sure. But when you spend a lot of time with bears, especially when you’re in the field with them day after day, there’s a siren song, there’s a calling that makes you wanna come in and spend more time in the world. Because it is a simpler world.

It is a wonderful thing, but in fact it’s a harsh world. It’s a different world that bears live in than we do.

So there is that desire to get into their world, but the reality is we never can because we’re very different than they are. The line between bear and human has apparently always been respected by the native communities of Alaska.

My sense is that the story of Kats and the bear helps steer people clear of the bear world, because you simply can’t go into it.

If we view the story of Kats as a mythological image of the perils of the shamanic career, on the other hand, then we’re presented with an archaic image of great power and authority. When we see the totem pole of Kats and his bear-wife, as we can see in the photograph above of the beautiful Tlingit pole in the village of Saxman, we respond to precisely the same image that we find in the bear paintings on the wall of the Chauvet cave – the same image that has spoken to people like us for tens of thousands of years.

Next time, we’ll have more to tell about Raven as a trickster figure.

References

1) Adapted from Boas F and Tate HW. Tsimshian Mythology. 1910. pp 58 ff.

2) See, for example, Clottes J and Lewis-Williams D. The Shamans of Prehistory. Harry N. Abrams. 1998.

3) Campbell J. The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. Penguin. 1969. pp. 339 ff.

4) Eliade M. Shamanism; Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press. 1964

5) Sidky H. Hunted by the Archaic Shaman; Himalayan Jhākris and the Discourse on Shamanism. Lexington Books. 2008.

6) Eliade, pg. 41

7) Eliade, pg. 49

8) Eliade, pg. 55

9) Campbell, pp. 334 ff.

10) See, for example, Boas F. Indianische Sagen von der Nord-Pacificschen Küste Amerikas. Verlag von A. Asher & Co. 1895. pp. 328 ff.

11) Sturlson S., trans. by Jesse Byock. The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. 2005. pg. 47.

12) Oberg K. The Social Economy of the Tlingit Indians. University of Washington Press. 1973. pg. 95.

All photos (C) Barnaby Thieme unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

Totem Poles of the Pacific Northwest

Note about Pictures: In order to make room for so many photographs, I’ve had to use thumbnails – I hope readers will click on some of them to see them full-sized.

The coastal region of the Pacific Northwest, stretching from the Alaskan panhandle in the north to Vancouver Island in the south, has been home to indigenous peoples for thousands of years, including the Tlingit (pronounced kling-KIT), Haida, Tsimshian and Kwakiutl.

These are different groups with distinct histories and languages, but they share deep similarities of culture, religion and art, which combine to constitute what the great anthropologist Franz Boas has called “one of the best defined cultural groups on our continent.” (Social Organization and Secret Societies of the Kwakiutl, 317) I will speak most frequently of the Tlingit, but draw upon other groups participating in this common cultural heritage as well.

One of the most striking features of this cultural zone is what we will call totem poles for lack of a better term. The word “totem” comes from the Ojibwe word for “kinship group,” and does not properly belong to the region. The Tlingit term is kootéeyaa, but several natives I have spoken with used the term “totem pole,” so I will follow their lead.

Originally, most totem poles were probably carved into the pillars of clan houses, like the great totems flanking the magnificent Beaver screen in the Tlingit Beaver Clan House of Saxman, Alaska (shown to the right). Short, free-standing totem poles were also placed in the woods, used to house the cremated remains of venerated persons.

When Russian and European fur traders arrived in the nineteenth century and metal tools became widely available, it became possible to carve much larger poles. These massive poles, sometimes dozens of feet high, were commonly erected along waterways, as the people inhabited narrow strips of land between the coastal mountains and the sea, or in densely-forested river valleys, and traveled by water.

The oldest surviving poles date to the mid-nineteenth century, and those are relatively few in number. Poles are usually carved of cedar, which does not preserve well. However, my understanding is that the demise of a pole is regarded as the completion of its life cycle, not a tragic loss.

Totem poles are emblazoned with figures called crests, which are usually animals, mythological beasts or legendary ancestors. Crests form an integral part of the social and symbolic economy of the Pacific Northwest and are core features of social identity. A crest may only be displayed by a family that owns the right to the crest, and those rights are passed down.

One interesting exception to that rule is the owl crest, shown to the right, which is not inherited and may only be displayed by a shaman.

Crests often signify historical or legendary episodes that help define the identity, status and privileges of a family. The world of songs, legends and myths is intimately bound up with crests, which may explain where the clan came from, why they have the right to fish in a particular stream, and so forth.

Let’s take a look at the striking Eagle Halibut pole of Laay, currently on display at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, to get a sense of how the symbolism works. The interested reader will find the full account of this complex pole here, but I will only focus on part of it.

To the right you will see two crests that combine to form a single composite image at the base of the pole. The smaller crest depicts a hero named Gunas being devoured by a large halibut, and that image is set onto the chest of a larger figure, an intense-looking figure called Hagwil̓ooḵ’ who carries a bent-wood box on his head.

This is a memorial pole for the Tlingit Chief Laay, who led his people out of their original home in Alaska to the village of Gwinwoḵ on the Nass River in Canada. While they were traveling to their new home, Gunas went swimming in the clear waters near Cape Fox, when he was suddenly attacked and swallowed whole by a giant halibut.

Richard Morgan tells the story:

Everybody got excited, you know, when they saw the huge halibut. They called for Supernatural Halibut and they called for Supernatural Eagle to help them. And the eagle [was] sitting right at the point, and the next thing you know, the eagle managed to get the halibut ashore and capture the halibut. And they cut the halibut open, but the body of Gunas, the remains of the body, [were] already decayed, so they sing a dirge song, funeral song about Gunas being captured alive by a halibut.

This account is typical of crest legends in several ways. It links an episode of the legendary past with a story and a song, and establishes the debt owed by the halibut to the clan. The Gunas crest connects the Nisg̱a’a Tlingit to halibut fishing – Gunas paid for the crest with his life. Crest stories frequently involve someone owing a debt, or violating a taboo or getting into a disagreement with an animal power or deity, and being killed. This death creates a new debt in the symbolic economy, and and the family earns the right to a story, or song, or place, or the right to hunt a particular animal, et cetera.

The concepts of debt and exchange are extremely important in the Pacific Northwest, as we saw previously when we looked at shame poles, which are erected to commemorate unpaid debts. The flip side of this is that if you want to fish, your family needs to have the moral right to fish, and it often seems to be established in stories of this kind.

There is a deeper mythological sense to this pair of images as well. Gunas and his halibut are engraved on the chest of this scary-looking Hagwil̓ooḵ’ fellow. Morgan explains this figure thusly:

And as they [were] traveling, they encountered a huge man from under water. It has a tail of a salmon. It came up with huge spring salmons, huge seafood, a lot of seafood. They call it Hagwil̓ooḵ’. That’s a symbol you will see on the bent boxes. Anybody who is really aggressive, get a lot of food for families, they call them Hagwil̓ooḵ’.

The paired crests of this pole combine the two aspects of the Great Hunt in a single image – we see both predator and prey. The Nisg̱a’a has paid for the right to catch fish with their own flesh and blood; that is, they belong to the cycle.

We’ve looked at this basic tragic image several times in this blog, most recently in the Grimm Brothers story “The Juniper Tree” here. We’ve also looked at the symbol as it was expressed in Iron Age Greece here.

The Eagle Halibut Pole of Laay illustrates the whole symbolic economy of the Pacific Northwest. Clans are characterized by the of symbols that encode their history and establish their rights and powers. These crests are not only displayed on house pillars and totem poles, but found on ceremonial chilkat robes or button blankets worn during ceremonial dances. A Tlingit can tell at a glance where someone is from and what their lineage is, simply be looking at their regalia.

Despite various historical challenges and setbacks, the symbolic culture of the Pacific Northwest remains vital and active to this day. While indigenous populations were decimated by exposure to Old World diseases such as small pox, the numbers have now stabilized. The United States abandoned its disgraceful campaign to eliminate native languages and cultures in the region decades ago, and since the 1960s there has been a great revival of interest in native art and culture. So the old arts are carried on – to the right you can see Tlingit Master Carver Nathan Jackson at work on a new pole in his studio. He was the lead artist of the spectacular Beaver Clan House screen shown above.

Many new artists appear to be interested in incorporating new sources of inspiration and ideas. For example, the superb Kwakwaka’wakw artist Doug Cranmer spent several years in the 1960s using traditional compositional elements of the Pacific Northwest to create entirely abstract work without story or reference. I also enjoyed the work of Averyl Veliz that I saw at the Juneau-Douglas City Museum, such as her wonderful “Wolf in the Moon” (right).

A great example of the harmonious blend of old and new is The Raven and the First Men by Haida artist Bill Reid, currently on display at the University of Anthropology in Vancouver. This magnificent carving depicts a Haida myth of Raven acting as a kind of midwife for the creation of humankind.

Raven is a powerful shamanic trickster figure and is the culture hero of the entire vast region from the Kwakwaka’wakw of Vancouver to the Inuit of Alaska. His stories are especially connected with acts of creation and naming, and the story of how Raven stole the sun from heaven and ended the long darkness is an extremely popular subject. In my next post on the Tlingit and other traditions of the Pacific Northwest, I’ll have a closer look at the mythology of the region, with particular attention to Raven.

The traditions of the Northwest remain with us. Bertha Sleid Guan of the Kaagwaantaan Tlingit told me that in her village, public schools offer classes in the Tlingit language every day, and once a week, the entire school day is conducted in Tlingit. She described her sense of wonder at seeing a young Tlingit girl speaking in her own language with her schoolmate, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl of Norwegian descent.

I told Bertha that I had read many wonderful stories of the old days, like the story of how the Tlingit came to move out of their ancient home in Glacier Bay, which I read in the superb book Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors by Norma Marks Dauenhauer and Richard Dauenhauer.

As Susie James told those authors, the Tlingit used to live in peace and abundance in Glacier Bay. At that time, there was a young girl who was kept in seclusion behind her house. We learn from many ethnographers such as Kalvero Oberg that this was a common practice when Tlingit girls approached adolescence. They were sequestered for months or a year in a private little hut behind the family dwelling until they were presented as adults at a great feast or potlatch.

But this girl was kept there for three years, which is a very long time. One day she saw a glacier very far away, and perhaps because she was unhappy with her seclusion, she called to it like a dog, saying “Glacier, here, here.”

To everyone’s alarm, the glacier started to grow, started to advance on the Tlingit, fast, faster than a dog could run. Everyone saw it charging toward them and they got into their boats to flee, to leave Glacier Bay and find a new place to dwell — everyone except for grandmother who didn’t want to go. She said “I will stay here. Whatever happens to my mother’s maternal uncles’ house will happen to me.” So she stayed and gave her life to the glacier, and there is our debt.

When I spoke to Bertha, I told her I had read this story, and I wanted to know, how do the Tlingit hold these stories today? Are they valued as legends, or are they believed, the way history is believed?

She told me that it may be hard for you to accept that a glacier would run as fast as a dog, but we’ve researched the area and we know that the Tlingit of her village came down from Glacier Bay, and they regard it as their sacred home. The archaeological evidence indicates that the area was inhabited around 2000 years ago by a people evidencing cultural continuities with the Tlingit of today, until they were driven out by a long period of ice. When the glaciers receded after the end of the Little Ice Age in the Middle Ages, the Tlingit appear to have moved (back?) into the area.

She told me that there are many stories that can be told to outsiders, like the ones I read in my book, and many songs that are sung for anyone. But then there are stories and songs that are private, known to the families and houses, and those stories have a lot to say about the world, and who we are.

All photos are (c) Barnaby Thieme, except “Wolf in the Moon,” which is my photograph of a work by Averyl Veliz, who retains all rights.

The Tlingit, the Raven, and a Shame Pole for Exxon

I’m going to be traveling with Ms. O’cosm and family to Alaska in July, and whenever I travel I like to read up on the history, mythology, and religious traditions associated with my destination. We’ll be sailing aboard a 63,000 ton cruise ship with ports of call along the Inside Passage, which has historically been home to a number of Native American tribes, particularly the Tlingit.

The Tlingit have a fascinating culture, and I’m thrilled that I’ll be able to visit with some craftsmen and cultural representatives in the town of Ketchikan.

A ubiquitous artifact of the native culture of the Pacific Northwest is the totem pole. To the right you can see a very old red cedar memorial pole (pts-aan), dating to circa 1870, which now resides in the British Museum.

Each figure on the pole represents a crest of the family or tribe. A crest is an animal or similar symbol which stands for a cultural artifact of some kind – a person, a story, a historical episode, what have you. A Tlingit pole, then, can present a collection of stories, events, and mythological episodes associated with a specific family or group. This particular pole was erected in memory of Chief Luuya’as and depicts crests from the Eagle-Beaver clan.

I was surprised to learn that the poles are sometimes used to mock or ridicule persons, who may be depicted in animal caricatures or upside-down. These shame pole, which usually depicts people who have refused to honor an obligation or debt, are displayed in public spaces. I learn from this Wikipedia article, for example, that the Three Frogs shame pole of Wrangell, Alaska, depicts three deadbeat dads who refused to pay support for their illegitimate children.

A shame pole was recently carved by Alaska fisherman and part-Tlingit Mike Webber, depicting Exxon CEO Lee Raymond upside-down, for refusing to pay court-awarded damages related to the Exxon Valdez spill. Peter Rothberg described the pole for an article that appeared in The Nation:

The pole tells the grim story of the spill: sea ducks, a sea otter and eagle float dead on oil. A sick herring with lesions is featured. There’s a boat for sale with a family crew on board, commemorating fishermen who went belly up, and a bottle of booze to remind people that Joe Hazelwood, who was captain of the Exxon Valdez, had been drinking before turning the helm of the ship over. Topping the pole is the upside-down face of former longtime Exxon CEO Lee Raymond, sporting a Pinocchio-like nose.

There are some wonderful resources on the web concerning the Tlingit, and other peoples in the region. The first I’d like to call attention to is the Internet Archive of Sacred Texts, which hosts an online copy of John R. Swanton’s Tlingit Myths and Texts, a superb collection of myths and legends from 1909.

I’ve been focusing on the enigmatic and complex trickster figure of the Raven in my reading. As Lewis Hyde copiously demonstrates in his fascinating study Trickster Makes This World, the trickster figure is associated with creation and demarcation in many cultures around the world, and this is certainly true of the Tlingit Raven. Numerous etiological legends associated with the Raven explain the origins of all sorts of natural phenomena. This archetype of the creative trickster is something I will return to in a later post.

Another terrific resource is the American Indians of the Northwest Collection, hosted by the University of Washington. This site features excellent essays and photographs from their archives.

Here’s an interesting account of Tlingit culture by Joe Williams, former mayor of Ketchikan:

Update:

I’ve now published a much more extensive look at totem poles and the cultures of the Pacific Northwest here.