The Orphan Hero

In contemporary popular society, most of the big heroes are orphans.

That may sound like a bold claim, but consider a few of the countless examples: Luke Skywalker, James Bond, Harry Potter, Superman, Batman, and Spider-man. How many blockbuster films do these six characters represent? I haven’t counted, but it’s around fifty, grossing many billions of dollars. That’s to say nothing of the books, comic books, toys, accessories and video games.

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy features not one, but two orphaned principle protagonists: Frodo Baggins and Aragorn. Tolkien was himself an orphan.

The ten highest-grossing films of all time, adjusted for inflation, are:

Gone with the Wind

Avatar

Star Wars

Titanic

The Sound of Music

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

The Ten Commandments

Doctor Zhivago

Jaws

Snow White and the Seven Dwarves

Both of young Scarlett O’hara’s parents die in Gone with the Wind. Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia are both orphans. Jack Dawson, played by Leonardo di Caprio in Titanic, was orphaned at a young age.

Maria von Trapp in The Sound of Music was an orphan, and the film is largely about the missing mother figure in the Trapp family.

Divorce and abandonment by the father feature prominently in E.T. The Wikipedia article on the film, with citation to the biography of Stephen Spielberg by Joseph McBride, states that the alien was based on an imaginary friend Spielberg invented after his parents’ divorce in 1960. “Spielberg said that E.T. was ‘a friend who could be the brother I never had and a father that I didn’t feel I had anymore.'”

Moses? Found in a river, raised by Pharaoh’s daughter. Yuri Zhivago? Orphan, taken in by his mother’s friends after she died. Snow White lived with her wicked stepmother.

That leaves only Jaws and Avatar. Jaws, I grant you, has no obvious connection to orphans. Avatar doesn’t deal explicitly with orphans, but the primary theme is about its hero finding his real family and true identity.

So, out of the ten top-grossing films of all time, seven of them are about orphans, and two of the remaining three (E. T. and Avatar) have core themes of child abandonment.

***

Clearly there is something about the orphan motif that works for people – so much so that it has become the acme of the hero category.

No single factor can account for this fact. However, several possibilities represented by the orphan character, both on the story level and symbolically, tend to work very well. I believe the combination of story opportunities that the orphan situation provides can account for the popularity of the type.

At the most basic level, the orphan arouses our natural sense of sympathy. Orphans are, after all, children who have suffered a great loss that anyone can understand.

In fiction, orphan characters often grow up feeling isolated and vulnerable. They may achieve wisdom and maturity beyond their years because of the hardship and loss they have had to bear at an early age.

The loss of the parent may give the orphan hero an idealistic commitment, as in the case of Spider-man. Peter Parker was orphaned a second time by the death of his kindly Uncle Ben – a death for which he bore some sense of responsibility. It is easy to accept that an experience like that could form a passionate commitment to justice that would change the course of his life, having learned from his uncle that “with great power comes great responsibility.”

We see similar developments at work in the comic book heroes Tony Stark (Iron Man) and Bruce Wayne (Batman).

As described in the Ian Flemming novel You Only Live Twice, James Bond lost his parents at an early age, leaving him a maladjusted youth who found a surrogate parent of sorts in his service to Queen and Country.

The longing for lost parents or the quest for a substitute reflects a universal longing for security and home. This mood is developed vividly in Dr. Zhivago, in which Yuri’s peregrinations reach an apex of poignancy when he returns to the childhood home where his mother passed away.

***

For those of us who are not orphans, the character may reflect the intuition that we live in a world filled with problems that our parents did not prepare us to confront. The new face of warfare, climate change, economic challenges and disasters – every generation finds itself in a brave new world, and anyone can be disillusioned by the world they inherit.

A world without parents is a world in which we are left to our own devices, and must understand and confront whatever dangers await us. This sense of peril and self-reliance is a central heroic theme. We see it developed, for example, in the Harry Potter series, in which Harry’s development is followed from his youth, during which he lives under the magical protections his parents and guardians bequeathed to him, to his maturity, in which he is increasingly exposed to danger, and must set things right through his own initiative and achievement.

This transition is dramatized by Harry’s confrontation with the newly-returned Voldemort at the midpoint of the saga, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.

Through a magical effect that Rowling calls priori incantatem, which is apparently Latin for “transparent plot device,” the ghosts (sort of) of Harry’s parents come to his aid at the moment of crisis. But when they depart, their protection is withdrawn. In the fifth and sixth novels, he loses his godfather and his mentor, and by the final novel, he is solely responsible for confronting the evil he finds in the world.

This theme finds an interesting parallel in the novels of James Joyce, which, it goes without saying, are creative works of an entirely different order. Nevertheless, the primary creative agent in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist and Ulysses is Stephen Dedalus. Although he has a father, and could even find a second in Leopold Bloom, should he wish to, he rejects both, preferring to create for himself a space without fathers; that is, without precedent or constraint, in which he can create.

In the symbolic language of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the rejection of the father is the slaying of the dragon, a beast who says “Thou shalt,” with its very being. This heroic deed is the necessary prelude to the creative life.

So, in many cases, the orphan embodies the self-reliant, creative adult. It is tempting to posit this as a particularly American idiom, one which reflects the country’s mythology of self-reliance, and its status as a land without history. This may be at work in some cases, such as Superman, who is arguably the quintessential hero of the 20th century. However, we also have the cases of the Irish James Joyce and the English Rowling, Flemming, and Tolkien.

***

On the mythological plane, the orphan is frequently a character of great and hidden ancestry or lineage, and it is often the discovery of the unknown lineage that sets the hero on their adventures.

We find this in Luke Skywalker, of course, who wants to learn the ways of the Force, like his father.

Harry Potter learns to his delight that he’s no mere Dickensian orphan, but a magician of proud parentage. Superman learns about his family on the planet Krypton when he comes to maturity, and this discovery sets him on his quest for truth, justice, and the American way.

The secret lineage motif represents the duality of our public and private identities. Our public face – or “secret identity,” in comic book language – is a socially-constructed, socially-approved fiction, in which we work menial jobs for the Daily Bugle or Planet, and have a hard time getting a date.

But in our actual, inner lives, and with respect to our true inheritance, we are luminous beings, the children of kings and gods, which are themselves merely mythological projections of idealized human values.

We could easily excavate countless exemplars of this motif, such as the Grail hero Parzifal of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s epic. Raised in the forest by his mother Herzeloyde, Parzifal knew nothing of his own heroic father Gahmuret, who was a famous knight. He did not even know of the existence of knights, until one day he stumbled upon one traveling through his forest.

Parzifal, the young rube, beheld the splendid knight in bright armor, and thought that he had met a god. And so he had, for here in outward form was the living reflection of his own inmost potential.

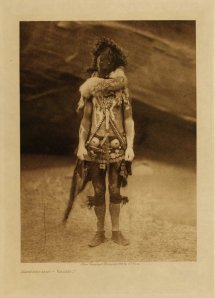

This motif is not confined to the traditions of Europe. In the mythology of the Apache and the Navajo, for example, the two great culture heroes are twins named Slayer-of-Monsters and Child-of-the-Waters. Accounts of their childhood differ, but in all cases they learn, upon reaching a certain age, that their absent father, whom they have never known, is the Sun, who dwells in his mansion far to the east.

So they begin their extraordinary journey to meet with their father. They overcome many obstacles on the way, and, when they reach that far-off mansion, they are tested by their father, who accepts them and teaches them the bow and arrow, and the names of the plants and animals, and how to behave like human beings.

I cannot help but be reminded of the Gospel of Thomas, in which it is written “When you know yourselves, then you will be known, and you will understand that you are children of the living Father.”

A lovely idea to consider on a rainy Saturday night . . . and beautifully written, too!

Jody Stefansson

December 1, 2012 at 8:43 pm

I have heard that Walt Disney understood that children 5-7 were preparing to start school and have to face the trauma of being away from Mom and parents around this age. Movies like Bambi were specifically geared toward helping kids understand that they could be alright on their own (and would be meeting new friends). Of course it’s also a natural start to place a kid on their own as a way to start an adventure story or epic quest (James and the Giant Peach, Lemony Snicket, Hansel and Grettle, The Lightening Thief, etc) if your target audience is kids.

Charles Thayer

December 14, 2012 at 10:16 am