Masks of God

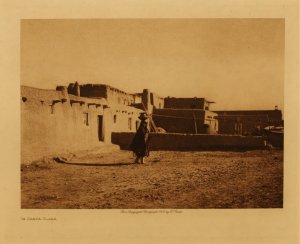

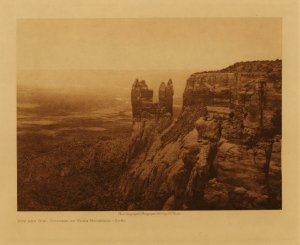

I’ve been studying the native peoples of the southwest United States – particularly the Zuni, the Hopi, the Navajo, and the Apache. There is so much I wish I could share with you about their marvelous cultures, but I’m afraid I’m just a simple blog writer and don’t have time to do it all. If you are interested in comparative religions, though, I heartily recommend you pick an angle and dive in.

I was recently struck by an exchange with a Zuni woman that was reported by Erna Fergusson in her book Dancing Gods; Indian Ceremonials of New Mexico and Arizona. She describes in rich detail the annual Shalako festival, in which a precession of masked dancers in beautifully-painted masks – some of them sixteen feet tall – enter the town and receive offerings.

These masked dancers are known to be members of the village, yet they are also viewed as gods, in some sense. They both are and are not the deities whom they “personate,” to use Fergusson’s apt term.

Fergusson reports:

The Council of the Gods comes annually to Zuñi and is received with the reverence due those in whom the divine is actually present.

We call these figures gods because Matilda Stevenson did so when she first wrote of them in 1879, but my informant, a very intelligent and well-educated Indian woman, refuses the title absolutely.

“They are not gods,” said she; “That word is wrong. The Zuñi have no gods; they are Ko-Ko.”

“Just so,” said I, expectant pencil poised; “And what is the English word for Ko-Ko?”

“There is no English word for Ko-Ko. I do not know. It is something different. I cannot tell you how it is to the Zuñi, but they are not gods.”

So there it is, as inexplicable as everything Indian must always be to the white man. They are not gods; they are Ko-Ko, and for Ko-Ko there is no English word, and presumably no English idea. It seems likely, from many similar conversations and a sincere effort to get the Indian point of view, that the Indian has no anthropomorphic gods. Yet such creatures as these of the Zuñis impersonate something divine: possibly merely an aspect of the great hidden spirit, which in one manifestation is so brilliant that the sun is a shield to hide it. (1)

Just as the men are not Ko-Ko, the Ko-Ko are not gods, but aspects of the divine, or, as Joseph Campbell put it, masks of God. These are symbols that invoke and instantiate a great mystery, and are recognized as such.

This reminds me very much of the bit of Ibn-al’Arabi that we recently looked at in a post on the artist Bill Viola. “God has seventy veils of light and darkness; were he to remove them, the glories of His Face would burn away everything perceived by the sight of His creatures.”

There is an endless process of deferment, where the symbol is not the thing, but stands in relationship to something else, which is also not the thing, because the real thing is beyond words and ideas.

Even among so-called primitive peoples, it is very common to find a high degree of epistemological sophistication about such matters. Only small children in archaic societies believe that people in masks are actually gods and monsters. Indeed, in many societies that celebrate ritual masked dances, the initiation that brings young boys into adulthood involves being tormented by masked figures, who are ultimately unmasked, so the young man can really understand what has happened to him – that the masks are symbols for the divine forms of the tribe. We can find such initiations in a great range, from the desert southwest of the United States to the aborigines of Australia.

Many of the cultures I’ve been studying lately engage in ritual dances, and looking at one after another really gets you thinking about sacred dance and its nature. I’m sure it will surprise no one to hear that many Christian missionaries believed the Indian sacred dances were diabolical and should be stopped. It goes without saying, but it’s also exceedingly odd.

“Worship is not to be done by moving your body; it is to be done by sitting in orderly rows in a building and singing,” says the pious missionary, and to him that makes perfect sense.

My cursory research on the topic suggests that the Christian church has long frowned upon dance, going all the way back to the bishops of Alexandria in the third century, who discouraged their congregations from dancing in celebration of the holidays. They recognized dances for what they were: popular continuations of practices that had long been enjoyed and valued. They were therefore to be distrusted.

One fine day long ago, when I was living at a Zen monastery in the mountains, I was on the serving crew. Our job was to serve lunch in an elaborate and painstaking ceremony called Ōryōki, which is a bit like Japanese Tea Ceremony. The serving of the food is tightly orchestrated, so that everything works like a Swiss clock.

At one point during the serving, I was hanging out a bit in the kitchen. I knew that I wasn’t due back at the meditation hall for a few minutes, so I was waiting and thinking.

Now, the fellow who was in charge of the crew saw me standing there and must have thought to himself, “What on earth is this monk doing?” He yelled at me “Get to the meditation hall! NOW!” and raced off.

I am so glad that he did this, because it produced a minor insight for me. Here, I realized, is a man who has lost all perspective.

What we were doing out there in the woods was essentially a form of theater for a very small audience: ourselves. And even if I dropped an entire pot of stew in the abbot’s lap, it wouldn’t have been that big of a deal.

That bit of perspective was invaluable, because all these forms of demonstrative worship are bits of theater we do for one another. The distinguished Zen scholar Carl Bielefeldt has in fact argued that the purpose of Zen meditation is merely to ritually re-enact the enlightenment of the Buddha, and nothing more. A lot of people don’t like that – they would like to see the Great Light or whatever.

I’m not sure what my point is exactly. What were we talking about? Ah – right, masks. It’s the masks that we all wear, and they seem very impressive. And they are, and they aren’t. There may be an opportunity here, to see that this personality I wear is also a mask, and is, in fact, a mask of God.

If you take off your own mask, you get to see that there’s nobody here but us, and then we can all relax a little. It’s pretty good.

Addendum (Dec 6, 2012): The famous Oglala Lakota medicine man Black Elk once told John Neihardt the story of how White Buffalo Woman brought the first sacred pipe to his ancestors. He then made this statement:

“This they tell, and whether it happened so or not, I do not know; but if you think about it, you can see that it is true.”

References

1) Fergusson E. Dancing Gods; Indian Ceremonials of New Mexico and Arizona. The University of New Mexico Press. 1931. p. 98.

Great thoughts Barnaby. I would guess Ko-ko is without equivalent to our monotheistic minds, simply because there is no good icon to represent our “all powerful, all know, all being”. While Judaism speaks of having aspects of the divine represented in parts of spirit, I think they are lost in christianity (cannot speak about Islam), yet even these are ephemeral. I think your term Masks of God is a good one. I’m curious what equivalents there are in animistic religions like Shinto, or other asian cultures where the gods are often represented with masks or mask like painted faces.

There is an interesting study of the body and movement in Morris Berman’s “Coming To Our Senses” that may give some further insight into the schism between archaic religions and christianity, as it studies the somatic basis of Western religious experience. For the most part the somatic aspect of Western religion is largely absent, having been marginalized or eradicated. As you know, experiential religion is frowned upon in the West, since it is not able to be controlled by those of the priestly cast who stand between the common human and the divine, mediating the omnidirectional transmission of spirit.

Jordan

November 13, 2012 at 9:42 pm

I think the problem here is that the Zuni woman assumed that the word “god” has a meaning in English. I submit it only has a meaning for people who don’t understand what the word means.

You’ve probably heard that story that Joseph Campbell likes to tell about the Christian priest who spent the day at a Shinto shrine, and said “I’ve seen some wonderful things, but I don’t think I understand your religion. I don’t understand your cosmology, I don’t understand your theology.”

The Shinto priest thought for a bit and said, “I don’t think we have a cosmology. I don’t think we have a theology. We dance.”

I think something like that is at work with respect to understanding the gods. In any functioning mythology or religion, the meaning of the symbol is complete in its expression. If you have to ask what a symbol means, then it’s no longer alive. It’s like a painting – no artist will tell you what a painting “means.”

When the Ko-Ko come, you offer them cornmeal and pollen. When they dance, you watch them. When they depart, you call after them your prayers for a rainy growing season. That’s it.

Mesocosm

November 13, 2012 at 9:55 pm